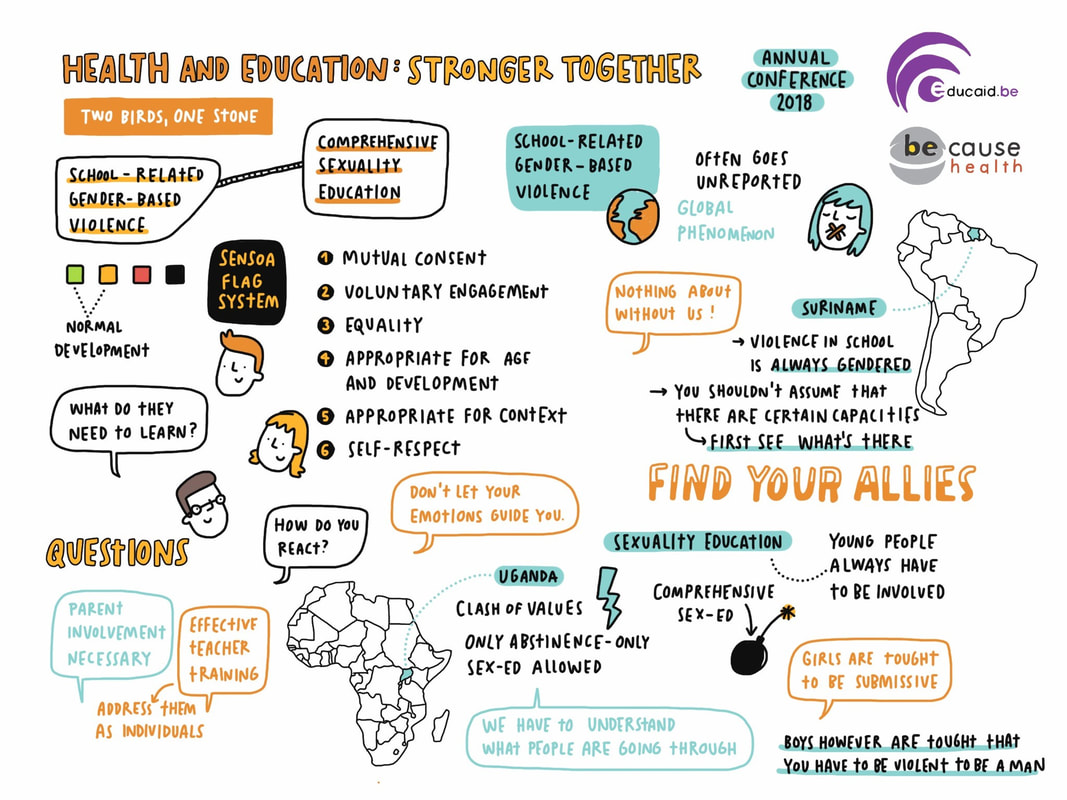

How can comprehensive sexuality education and programmes addressing school-related gender-based violence contribute to better sexual and reproductive health and education outcomes? These questions were at the heart of the ‘Two birds, one stone’ Panel, at the Educaid-Because Health conference “Health and Education: Stronger Together” at the Egmont Palace, on May 17th, co-organised by Sensoa.

Karen De Wilde, trainer at Sensoa, kicked off the session by introducing the audience to the Sensoa flagsystem, a tool developed to prevent sexual transgressive behaviour and to support the healthy sexual development of children and young people. Green, yellow, red and black flags went up in the air, when the audience was confronted with different hypothetical, yet concrete situations of sexual behaviour. The panel of experts discussed the use of the system and pointed out its strengths. The system is particularly helpful to engage in a dialogue on sexual behaviour and to discuss concrete experiences and how to intervene (or not). It has proven to work as a pedagogical model, that allows us to understand what a child needs to learn. It can also help children understand when their rights are being violated.

VVOB-Suriname has adopted the flag system in its training of teachers in vocation schools, where sexual transgressive behaviour has shown to be particularly challenging. Engaging professionals, parents and pupils with the flag system turned out to be much more than simply implementing a programme. It led to discussion, exchange and negotiations with a wide range of stakeholders, which helped to build support for more structural change.

Joanna Herat, Senior expert on health and education for UNESCO introduced the updated UNESCO guidance on comprehensive sexuality education. The guidance presents the ‘ideal scenario’ but not a single country lives up to that. The guidance is thus aspirational and helps to find the entry points to build a curriculum. Experience has shown dialogue with parents, religious leaders and young people to be crucial for the success of CSE. Equally so, teacher training is quintessential, as many teachers feel uncomfortable to actually take up CSE and many of them never received CSE themselves.

Anna Ninsiima, PhD researcher at VUB and lecturer at the School of Women Studies and Gender at Makerere University in Uganda shared her insights on the challenges to implement CSE in her country. Uganda has een fierce resistance to CSE. Sexuality education at school does exist, however, it is confined to the promotion of ‘abstinence only’ and schools are not allowed to teach anything that is not endorsed by the government. In Uganda, the ‘C’ in CSE is understood to stand for ‘the promotion’ of homosexuality, masturbation and abortion, and consequently going against cultural and religious values. But there is more that complicates the implementation of CSE, Ninsiima pointed out. In CSE the importance of access to SRH services is underlined, yet, the country’s poor health systems cannot provide for that. Equally so a strong educational system is lacking, which the implementation of CSE requires. Also, when promoting ‘rights’, this means that one’s rights should be protected and due process guaranteed. However, faced with corrupt police officers, victims of sexual violence might have no one to run to.

Gender inequalities also affect the extent to which talking about ‘rights’ makes sense. “How are girls to build self-esteem and exercise their rights if they are being told that, as a girl, they have nothing to offer? Or if schools teach girls to be submissive? Then how is one supposed to defend oneself?”, Ninsiima asks. Most girls’ first sexual experiences are coerced. They think they need to have sex for the sake of someone else, and not their own, their own feelings or their own bodies. The idea that women ‘give’ and men ‘receive’ is normalised and this makes it difficult to convey emancipating messages to both women and men, girls and boys. Only a holistic approach that addresses these different challenges will allow CSE to be successful.

VVOB-Suriname has adopted the flag system in its training of teachers in vocation schools, where sexual transgressive behaviour has shown to be particularly challenging. Engaging professionals, parents and pupils with the flag system turned out to be much more than simply implementing a programme. It led to discussion, exchange and negotiations with a wide range of stakeholders, which helped to build support for more structural change.

Joanna Herat, Senior expert on health and education for UNESCO introduced the updated UNESCO guidance on comprehensive sexuality education. The guidance presents the ‘ideal scenario’ but not a single country lives up to that. The guidance is thus aspirational and helps to find the entry points to build a curriculum. Experience has shown dialogue with parents, religious leaders and young people to be crucial for the success of CSE. Equally so, teacher training is quintessential, as many teachers feel uncomfortable to actually take up CSE and many of them never received CSE themselves.

Anna Ninsiima, PhD researcher at VUB and lecturer at the School of Women Studies and Gender at Makerere University in Uganda shared her insights on the challenges to implement CSE in her country. Uganda has een fierce resistance to CSE. Sexuality education at school does exist, however, it is confined to the promotion of ‘abstinence only’ and schools are not allowed to teach anything that is not endorsed by the government. In Uganda, the ‘C’ in CSE is understood to stand for ‘the promotion’ of homosexuality, masturbation and abortion, and consequently going against cultural and religious values. But there is more that complicates the implementation of CSE, Ninsiima pointed out. In CSE the importance of access to SRH services is underlined, yet, the country’s poor health systems cannot provide for that. Equally so a strong educational system is lacking, which the implementation of CSE requires. Also, when promoting ‘rights’, this means that one’s rights should be protected and due process guaranteed. However, faced with corrupt police officers, victims of sexual violence might have no one to run to.

Gender inequalities also affect the extent to which talking about ‘rights’ makes sense. “How are girls to build self-esteem and exercise their rights if they are being told that, as a girl, they have nothing to offer? Or if schools teach girls to be submissive? Then how is one supposed to defend oneself?”, Ninsiima asks. Most girls’ first sexual experiences are coerced. They think they need to have sex for the sake of someone else, and not their own, their own feelings or their own bodies. The idea that women ‘give’ and men ‘receive’ is normalised and this makes it difficult to convey emancipating messages to both women and men, girls and boys. Only a holistic approach that addresses these different challenges will allow CSE to be successful.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed